History of Forest Glen

Forest Glen (“The Glen”) is a small community of about 550 families on the Northwest side of Chicago. Its southern boundary is Foster Avenue. Forest Glen Avenue forms the northern boundary and then turns to become its western length. Cicero Avenue borders the neighborhood on the east. Forest Glen’s history has played a unique part in Chicago’s heritage.

The Pottawatomie Indians inhabited the area in the 17th century. These indigenous people migrated to this area because of its plentiful forests and natural resources. They settled along the northern branch of the Chicago River, which flows due east through the northern section of the Glen. The first man given official claim to Forest Glen was Billy Caldwell, also known as Chief Sauganash, who was born in Canada around 1780. His mother was a Pottawatomie Indian and his father was an Irish officer in the British Army stationed in Detroit.

During the Fort Dearborn massacre in 1812, a monumental event in Chicago’s history, Sauganash was instrumental in saving the lives of the historical John Kinzie family, as well as those of others. In recognition of his services, Sauganash received the forest land that includes modern-day Edgebrook, Sauganash and Forest Glen from the U.S. government, an area marked today by the line of Rogers Avenue, Forest Glen Avenue and Forest Preserve Drive. Modern old-timers in Forest Glen can remember a bent tree trunk that was used as a boundary marker at Rogers and Forest Glen Avenues.

A meeting of the tribes was regularly held in Caldwell’s Reserve under the Old Treaty Elm, which stood at the corner of Rogers, Kilbourn and Caldwell Avenues until it died and was cut down in 1933. Marking the exact spot today is a bronze marker reading: “Old Treaty Elm. The tree which stood here until 1933, marked the Northern Boundary of the Fort Dearborn Reservation, the trail to Lake Geneva, the center of Billy Caldwell’s Reservation, and the site of the Indian Treaty of 1835. Erected by Chicago’s Charter Jubilee. Authenticated by Chicago Historic Society, 1937.”

Caldwell and his wife built their home on the brow of the hill on the north side of the Chicago river, near what is now Devon Avenue and the river. Early settlers referred to this area as “up at the clearing” and it was thought of with great respect. According to Laura Adams, whose father came to the area in 1858, Caldwell managed to lose claim to the property, and it reverted to the government.

Caldwell Avenue was a “half road,” extending as far as Grosse Point Road from Cicero Avenue. A favorite Sunday afternoon treat was a buggy ride out on Caldwell Road, gathering hazelnuts from the bushes.

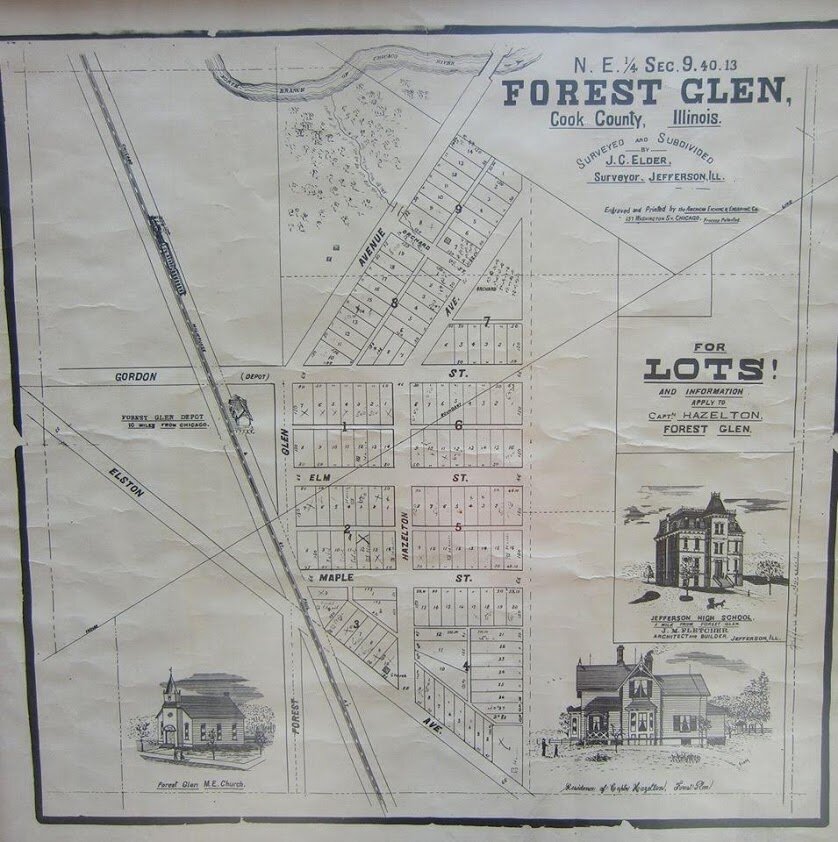

The second official owner of Forest Glen was Captain William Hazelton. He acquired the land as his Civil War settlement in 1866. He had a humble house and barn located north of Elston Avenue. It stood on a lane located roughly where Lawler Avenue now lies in the Forest Glen section of Chicago. He built the Glen’s first farm and orchard, becoming the chief supplier of cherries for the Chicago market. Hazelton built the first grocery store on the west end of Elston Avenue in 1865, near the crossing of the Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul Railroad. He established the community of Forest Glen, near Elston and Forest Glen Avenue in the early 1880s.

Hazelton, William Gray of the Schurz High School area and Lyman Budlong of the Budlong Woods area were all members of the Jefferson Township committee that opposed creation of Norwood Park Township in the 1870s. The annexation of Jefferson Township brought the old Caldwell Reserve into the city of Chicago. But it took the vision of Arthur Dixon, a retired Chicago alderman, to trigger the first residential subdivision in the forest in 1894.

A Swedish family, the Andersons, lived in the area with Captain Hazelton’s family. The Captain and Mr. Anderson were good friends and decided to live as neighbors in the Glen. Captain Hazelton decided to start a community and with his neighbor’s help began the task of establishing a small commonwealth. First, they went to the banks of the river and gathered as many elm and oak seeds as they could carry. By planting these seeds in an orderly fashion, they laid out the streets of the community. Captain Hazelton had become a subdivider.

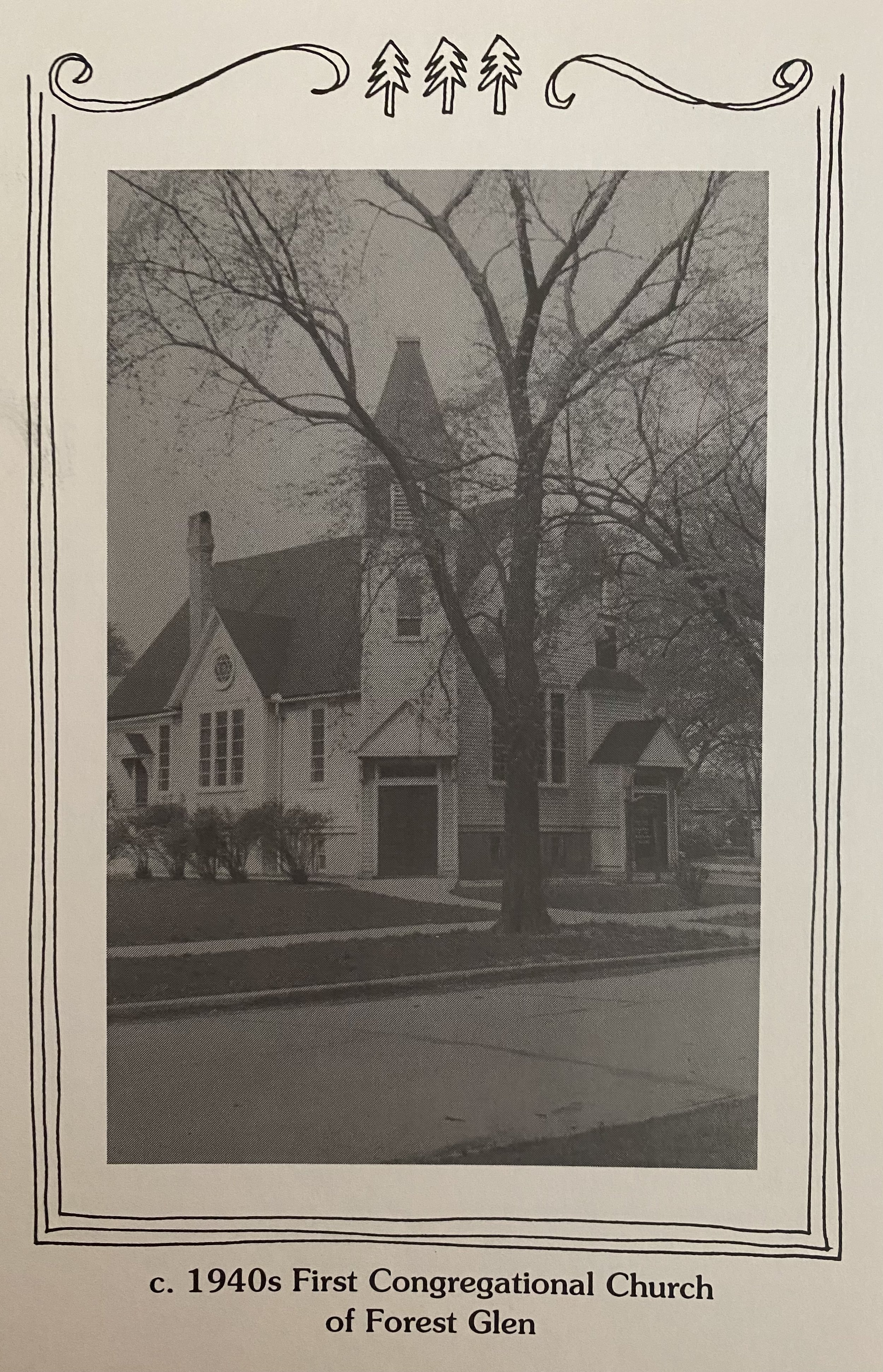

The Captain built a Congregational Church for his own faith and gave property to Mr. Anderson so that he might build a Swedish Methodist Church for his faith. This Methodist church, organized in the 1870s, was the oldest in Illinois until it was torn down and replaced by the Forest Glen Funeral Home in 1976. The original Congregational Church, at the same spot the present Congregational Church stands today at the corner of Lawler and Catalpa, was destroyed by fire in 1955.

The Congregationalists, being primarily of Puritan descent, were an austere group of people. Captain Hazelton did not allow smoking or drinking in his community and before accepting any family as part of the group he would carefully interview them and either accept or reject them as he saw fit. This practice helped account for the slow development of the community in its relation to the city itself. Forest Glen was one of the last neighborhoods to be annexed as part of Chicago, in 1889. Captain Hazelton was still screening possible occupants of Forest Glen at the time of his death in 1918.

President Teddy Roosevelt organized the U.S. Forest Service in 1906, and as a part of this conservation program, some of Captain Hazelton’s land was taken back by the government. Today those lands make up the Forest Glen, Indian Boundary, Billy Caldwell, LaBagh Woods and Gompers Park forest preserves.

Captain Hazelton was a shrewd businessman, and in an attempt to increase his market for cherries, finally persuaded the railroad to run a line through his property. This helped the population to increase and resulted in more home building. Rumor has it that Captain Hazelton’s deal with the railroad specified that if the Forest Glen train stop were ever to be removed that ownership of the land would revert to Hazelton’s heirs.

By 1920, the Forest Glen Forest Preserve had become the center of social events with all parties and celebrations taking place there, like a town square. Although part of the city, Forest Glen was (and in many ways still resembles) a small rural town. Everybody knew everyone else and many of its people were born, lived, married and died in the Glen.

After the Great Depression of 1932, a son of Mr. Anderson tore down his livery stable and general store and built a park in its place. He hoped that people of the Glen would use this area as their new center of social activity. However, his plan failed because the park was too small to satisfy all the needs of the district. This park stands today near the corner of Elston and Forest Glen avenues and is a playground for children. Around this time, a men’s pinochle club decided to form a community club, which continues today as the Forest Glen Community Club.

In an effort to reestablish the forest preserves as a community social center, men of the neighborhood (with the help of the 45th Ward Office) built an ice-skating rink in the forest preserves in December 1963 for the children and adults of the Glen. In 1970s, the Community Club started a campaign to save its numerous Dutch Elm trees from the threat of disease, but to no avail. By 1974, almost 600 trees were replaced, with several varieties represented so that no disease could again destroy all the trees.

At the end of the 20th century, Captain Hazelton’s and Mr. Anderson’s houses still stand. Ancient elms survive in small numbers. Part of Chicago’s colorful heritage still lives in Forest Glen and creates a sense of belonging to a fine community. Even its streets names represent history. Cicero Avenue was named after the Roman orator who opposed the crowning of emperors and favored a republic; Edens Expressway, named for William G. Edens, a banker and pioneer road developer; Elston Avenue was once an Indian trail but now memorializes Daniel Elston, a soap manufacturer and alderman of the 1840s. Other names like Foster, an important doctor of the early 1830s, and Milwaukee Avenue which means “good earth” or “good country” also show the spirit of the people from times long past.

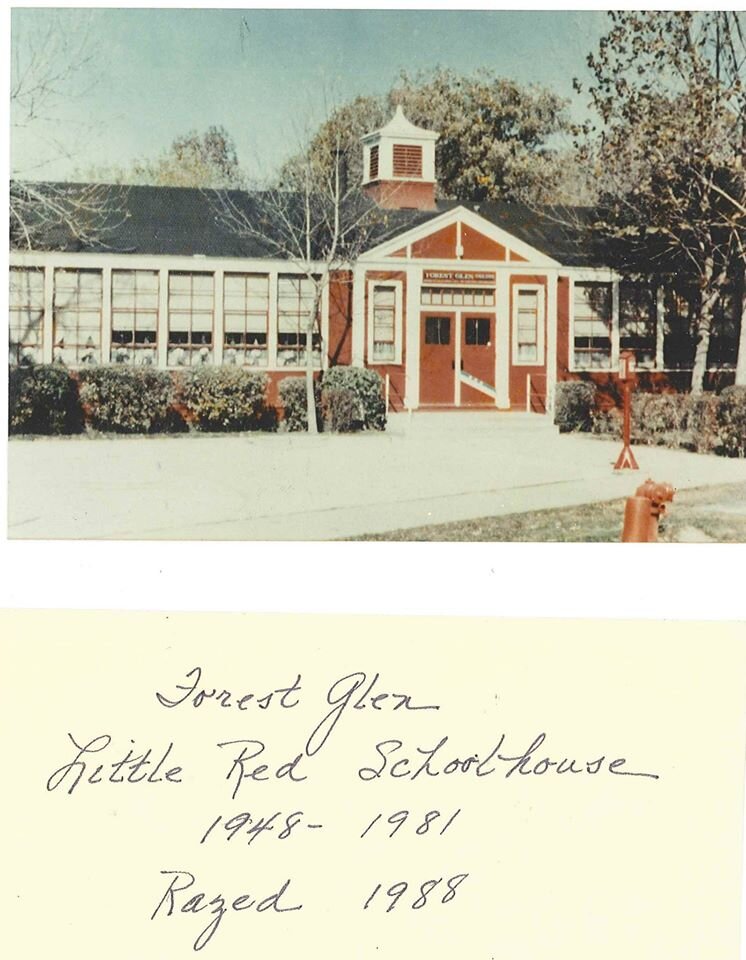

Homes in the Glen are Midwestern eclectic with cottages, bungalows, ranch houses, English Tudors and Georgians. Much of the neighborhood housing was developed in the 1940s, and it was not uncommon in the 1990s for the original owners to still occupy their homes. Forest Glen has not won a National Heritage designation, but there are indeed such dear landmarks as the “windmill house” and Captain Hazelton’s (still so dubbed despite the name of the current owners) once imposing residence. Our turn-of-the-century train station fell to the wrecker’s ball, as did the Little Red Schoolhouse on Bryn Mawr Ave., but they remain monuments in our minds.

Summer brings us to the field for picnics, softball, volleyball and camaraderie. As a community, we’ve gathered on the Fourth of July for a parade since the mid-1950s and have often held a picnic afterward in the Forest Glen Woods. It is no longer a difficult journey to downtown Chicago thanks to our Metra stop and close proximity to the Jefferson Park el station. We’re proud of our small, relatively hidden, and close-knit community of Forest Glen.

Created from papers received from: The Chicago Historical Society; Rev. Winfield Hall, former pastor of the Forest Glen Congregational Church; William Schueler of LaPorte Avenue; and Mary Wiedlin and Bob Buhl of Balmoral Avenue.

Tales of Forest Glen

We want to hear from former and current residents! Please send a fond memory or favorite photo to forestglencommunityclub@gmail.com